Exhibition

Freedom: Origin and Journey

Freedom: Origin and Journey is dedicated to the thousands of unsung lives given in the name of freedom and equality.

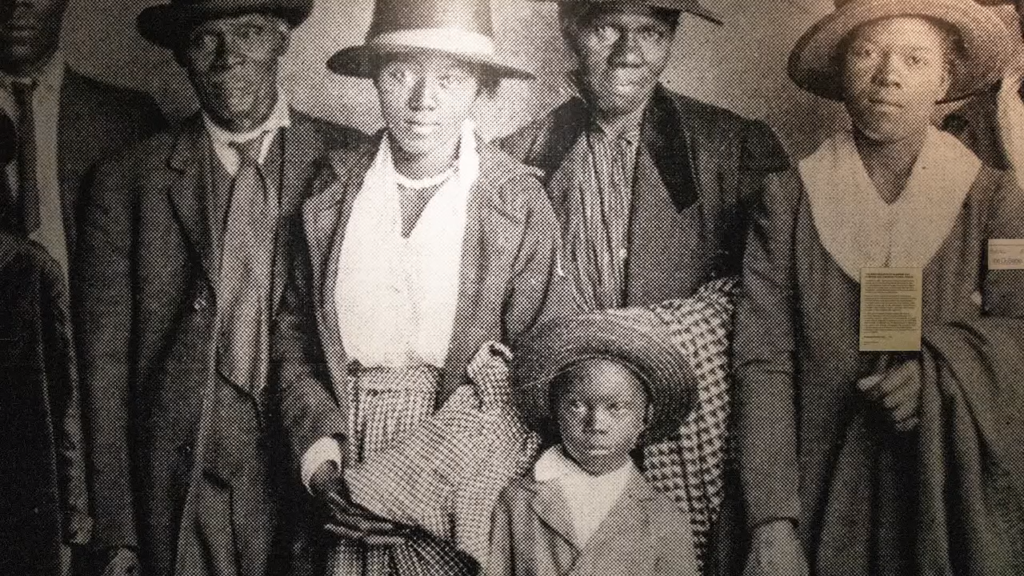

This exhibition has been designed to take visitors on a journey through the African American experience addressing several key periods throughout history that many visitors have come to anticipate being a permanent fixture within a culturally specific institution such as the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center. The visitor will begin at the apex of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and journey through the chattel slave system in the Americas.

Visitors will then move through Reconstruction, the Great Migration and view the height of the Jim Crow era of racial segregation in this country. At this juncture, the exhibition will deliver the audience into the aggregate, parallel tracks of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement as they unfolded throughout the 1960s and 70s. Visitors will learn about the achievements and setbacks of the 1980s and 90s before ending their experience at the dawn of the 21st Century as the country elected its first African-American President.

“Freedom: Origin and Journey” will prompt visitors to come face-to-face with American history illustrated by the use of 200 objects, artifacts and archival videos and images. Also, with the advancement of exhibition design and interpretation techniques, this exhibition will provide visitors, with the level of storytelling and depth of the Museum’s collections as it relates to the future.

Video Voice Credit: Detrice Ward

Online Exhibit

RESISTANCE AT SEA

REBELLION DURING THE TRANSATLANTIC

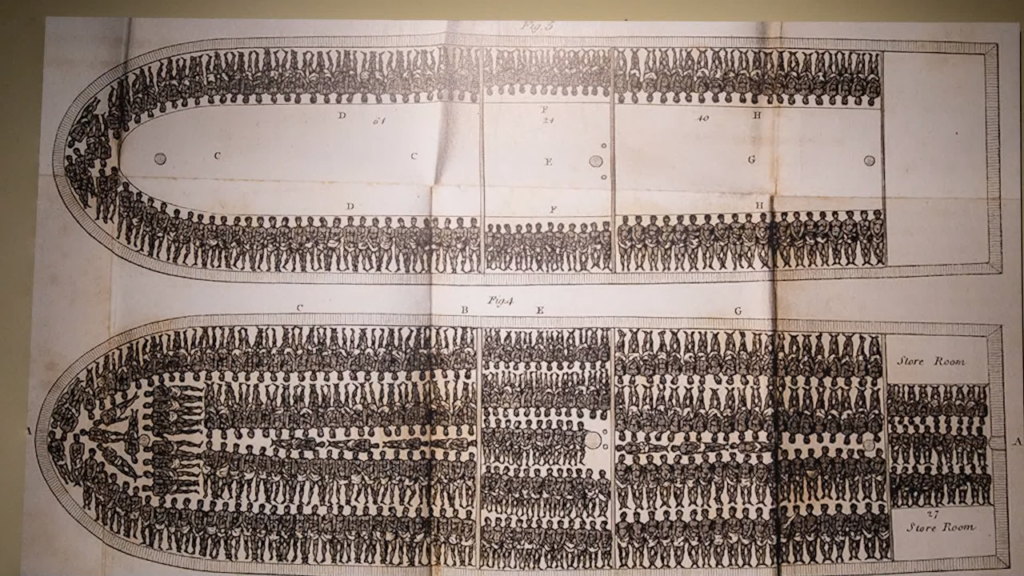

Transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people that carried 345 slaves from the coast of Africa, mainly to the Americas.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Between 1526 and the mid-1800s, over 10 million Africans were kidnapped and transported to the New World via the transatlantic slave trade. This forced migration marks the beginning of a widespread African diaspora, as those captured were taken from numerous ethnic groups across the West African coastline, packed onto European slave ships, and redistributed throughout the Americas and the Caribbean. Unaware of what awaited them and constrained under deplorable conditions below deck, many Africans resisted their situation, and the threat of rebellion on board these slave vessels remained high. In efforts to discourage uprising, both at sea and on land, “slavers” imposed sophisticated means of restraint upon individuals, as well as establishing dominance through public retribution. The punishment meted out was often a display of psychological control as much as it was physical. The public demonstrations were a particularly effective deterrent to others considering resistance or escape.

Leg Shackles

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Despite efforts to suppress revolt, there were thousands of recorded at-sea uprising over the legal lifetime of the slave trade, and later even more reports of newly arrived Africans fleeing as soon as they reached American soil. For those who remained captive, the diverse customs and trades brought from their homeland would prove vital to Southern plantation life.

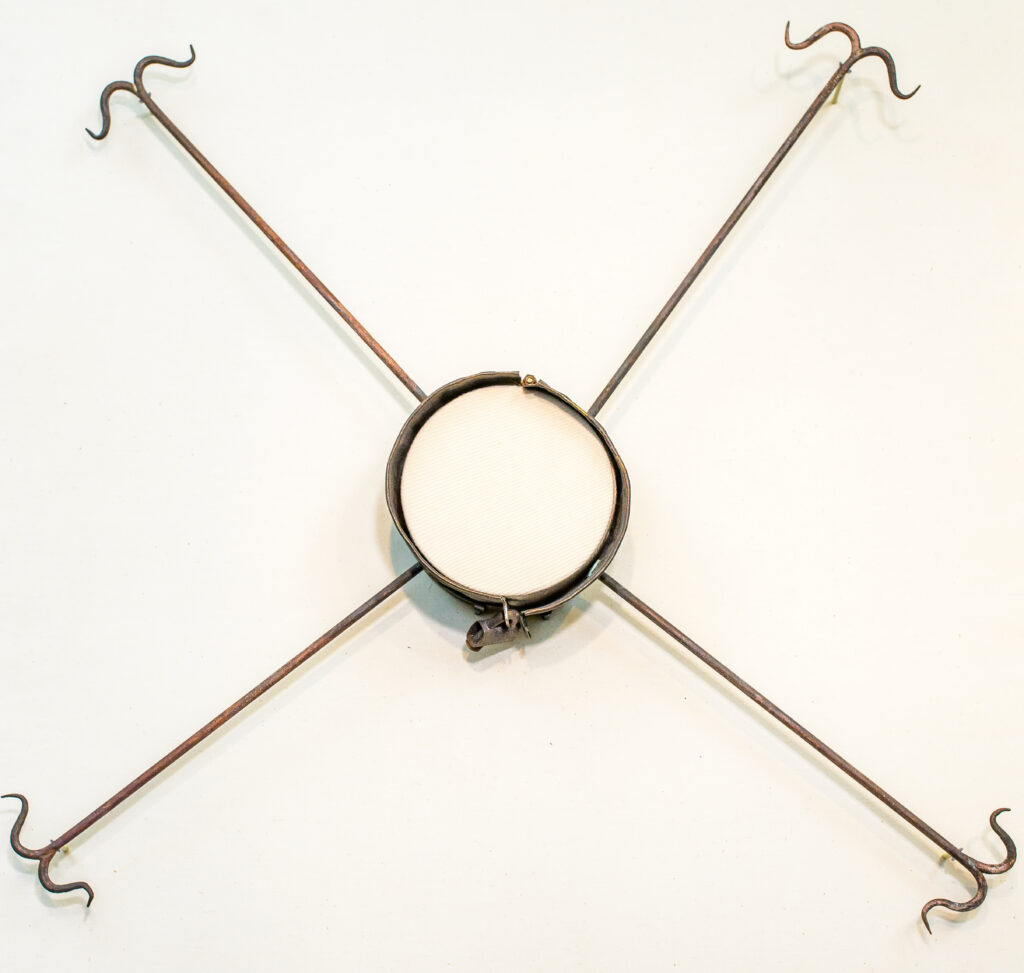

Upon capture, Africans found themselves bound with heavy shackles, bilboes, or collars. Leg irons like those seen here caused near-immobility and eliminated the ability to run. Neck shackles were attached to a chain that was then connected to the restraints at the wrists.

Slave Collars – Iron collars like this one could be used to punish enslaved individuals for a number of transgressions. The spiked arms caught on branches and brush, making escape difficult, and also made resting or sleeping lying down nearly impossible. The collar further served as a warning to others considering escape.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Freedom Deferred

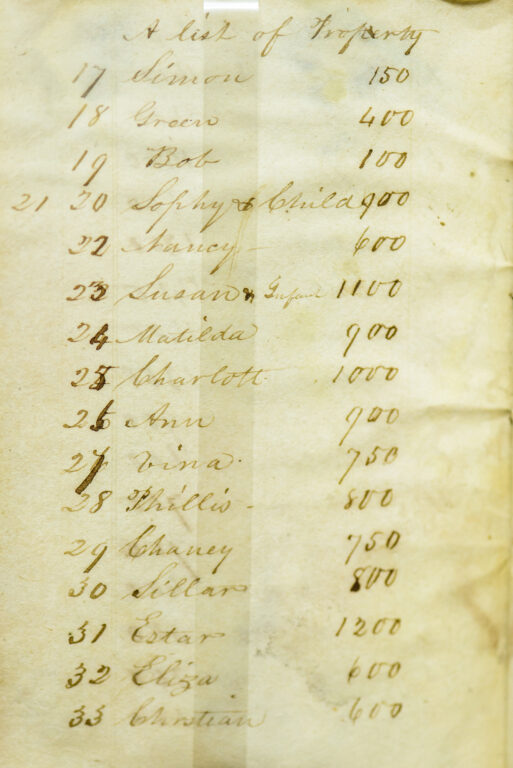

Plantation pocket journal, 1836

This small journal belonged to a slave owner named William Hale and includes “A list of Property.” The property recorded includes a number of slaves, their age and their monetary values.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center Purchase

In early America, slavery existed throughout the thirteen colonies and beyond. Although the colonies declared independence from Britain in 1776, this had little impact on the lives of those enslaved. For them, national liberty meant neither citizenship nor personal freedom. Slavery remained widespread across the young and growing nation, spilling into new territories as they developed and became states. However, the Southern states held the highest concentration of slave labor. Within these planter communities cotton was the ultimate cash crop, along with rice, tobacco, and indigo.

Hand-stitched quilt cover, late 19th century Born into slavery, Melvina Young likely created this quilt cover as free person, having been emancipated after the Civil War ended. Many enslaved people worked in the homes of the plantation owners. A common domestic role was that of seamstress, and Ms. Young probably learned to sew and quilt while working in her owner’s Tennessee home. Gift of Daisy Lewis in Memory of Melvina Young

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Many skills were needed to keep plantations running and profitable. In addition to field laborers, farms depended on trained carpenters, blacksmiths, gardeners, and grooms. Domestic work in a plantation owner’s home required proficient seamstresses, cooks, valets, caretakers, and repairmen.

Slave Tag 1857

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Learning trades often afforded slaves some degree of freedom, as many owners hired out surplus laborers. This practice sent slaves as close as the nearest plantation or far beyond state borders. The enslaved could also hire themselves out, an arrangement that gave some the means to buy their own freedom.

Charleston was unique among Southern cities for its formal badge system. Hired-out men and women wore tags like this one as identification. Servants and porters were two of the most common categories of slaves for hire.

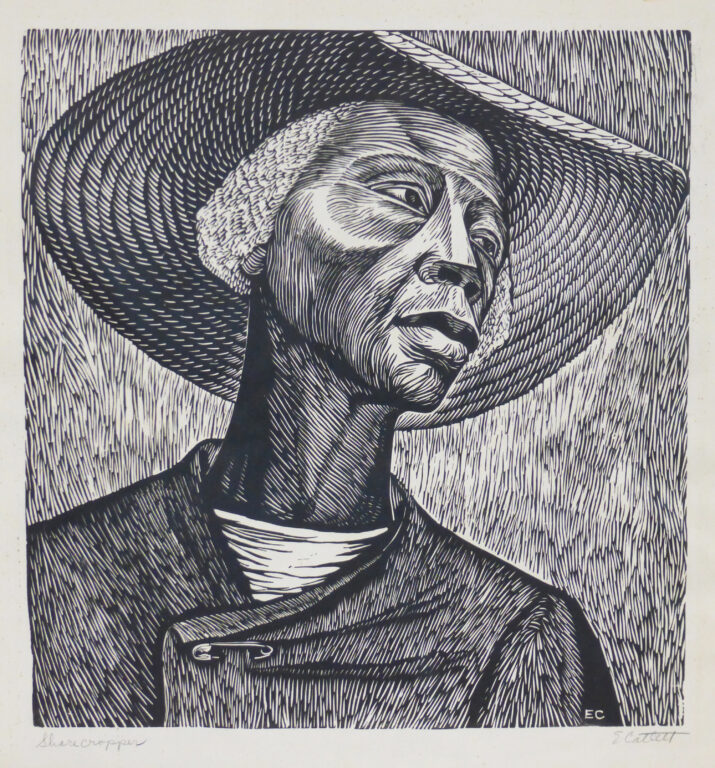

Sharecropper (1952) by Elizabeth Catlett, DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

The Thirteenth Amendment legally abolished slavery in 1865, ushering in a twelve-year “Reconstruction Era” during which African Americans gained voting rights and equal protection under the law.

However, limited options and resources meant that many stayed on the same plantations where they had been enslaved. They farmed plots of land and paid landowners with a share of their crops. After a bad harvest, sharecroppers could fall deeply in debt to landowners, who extended credit to them at inflated interest rates.

Sharecropping continued well into the 1900s.

The Jim Crow South

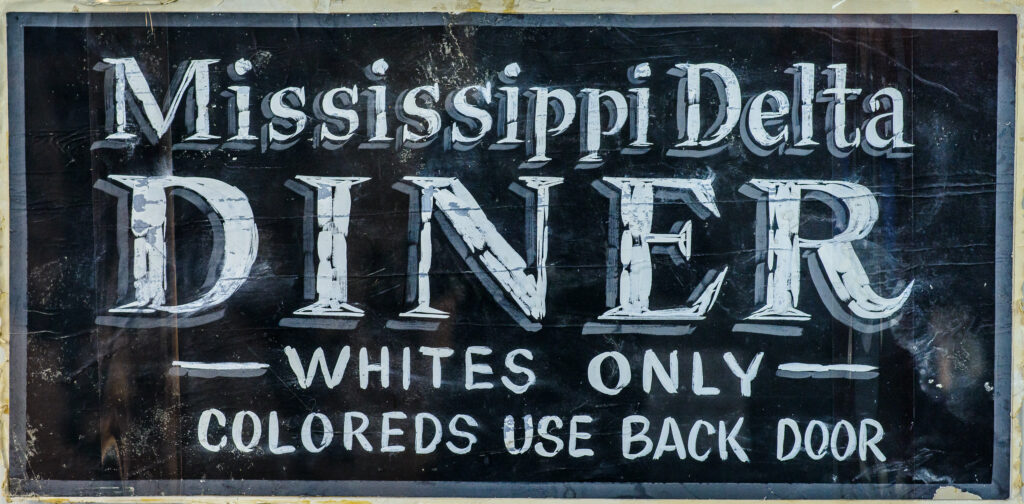

“Mississippi Delta Diner” Sign

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

The “Jim Crow” laws that appeared after Reconstruction took their name from a derisive term for African Americans, shorthand for a host of racial stereotypes. These laws, enacted throughout the South at the state and local level, codified white supremacy by eroding Black voting rights and enforcing segregation of businesses and public services. The 1896 ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson gave legal backing to states that provided “separate but equal” public facilities, such as schools and train cars. In practice, Black facilities were rarely equal to those provided to their white counterparts.

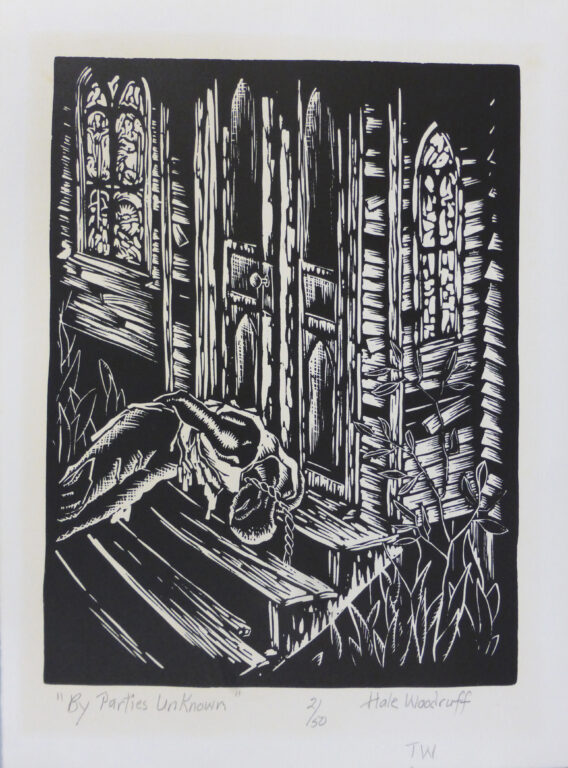

By Parties Unknown (1935 – 1981) by Hale Woodruff

suggestively juxtaposes a church, the pillar of both Black and white Southern respectability, with the horrific violence implied by the body laid on its steps. DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Informal and illegal methods of oppression also existed in the South, aided by the removal of federal protection for freedmen in 1877. Racial violence was pervasive, especially in rural areas. Any accusation against an African American could incite a deadly lynch mob or race riot. According to the Tuskegee Institute, between 1882 and 1968 nearly 3,500 lynchings occurred in the U.S.

The Great Migration

Robert S. Abbott, Founder of the Chicago Defender by William McBride

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

By the 1900s, Southern violence and inequity had spurred a “Great Migration” of African American workers and families leaving the South in pursuit of a better life. The Chicago Defender, an influential Black newspaper, urged its readers to head North. It also facilitated their journey by publishing train schedules, job listings, and other resources. By 1950, 2.7 million had relocated to cities in the North and West. Among them was young William McBride, whose family came to Chicago from New Orleans in the 1920s. McBride became an artist and later depicted the Chicago Defender’s founder, Robert S. Abbott, in the painting seen here.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Cities such as New York, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles received huge numbers of migrants. Though their arrival was often met with hostility, discrimination, and even violence, it also gave rise to a rich Black cultural movement. Its New York epicenter – later called the Harlem Renaissance – brought together some of the most talented writers and artists of the interwar period and left an enduring mark on younger generations of Black artists, including Jacob Lawrence.

Empowered by an ever-strengthening sense of community, African Americans also organized politically to confront the injustices that deprived them of their civil liberties.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

The Pullman Company employed thousands of African American men as porters for its railroad cars. Such work offered a path to the middle class and was less dirty, dangerous, and punishing than other jobs available to Black laborers at that time. Yet the Pullman Porters’ impeccable dress and manner belied humiliating treatment from employers and customers. They often worked long hours for low wages, with little recourse for seeking better conditions.

In 1925, the Porters formed a union. After years of negotiations, the Pullman Company finally recognized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1937. This hard-won success had a lasting impact on the struggle for labor and civil rights.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

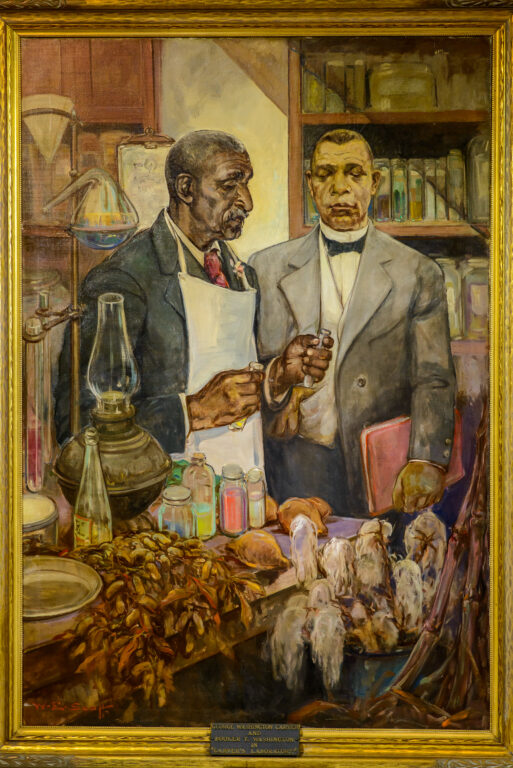

Activists and educators wrote, spoke, and organized in response to racial injustice and brutality. However, not all agreed on strategy. Booker T. Washington (depicted here with George Washington Carver) argued for accepting segregation as a necessary evil, prioritizing hard work and self-determination. Younger leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois rejected this approach, insisting on full political, economic, and social equality.

Despite the divide, Black activists formed several key organizations during this period, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which is still active today.

This writing desk is from the South Side home of Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Born into slavery in 1862, Ida B. Wells-Barnett became a key crusader for justice under Jim Crow. At 22, she sued the Memphis and Charleston Railway for ejecting her from a segregated train car. In 1892, she left Memphis under threat of violence for denouncing lynchings in the Free Speech, a Black newspaper she co-owned and edited. Settling in Chicago, Wells wrote and lectured about racial violence, women’s rights, and other issues until her death in 1931. Perhaps her most groundbreaking work was The Red Record (1895), an analysis of recorded lynchings and their alleged causes.

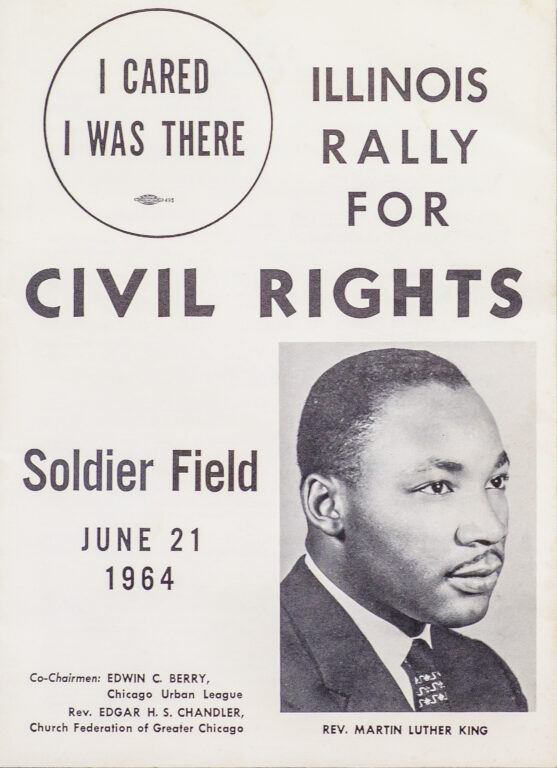

Flyer, Illinois Rally for Civil Rights (June 21, 1964)

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

The Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century built on the work of earlier activists to gain critical momentum. Accounts of racial violence and injustice – such as the 1955 murder of Emmett Till – galvanized students, politicians, and organizers to push for radical change. Tactics included boycotts, sit-ins, marches, rallies, and strikes. One of the Movement’s greatest leaders, Martin Luther King, Jr. advocated a strategy of nonviolent resistance, shown through actions such as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Montgomery Bus Boycotts, and Selma to Montgomery Marches. The work of King and others spurred the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965.

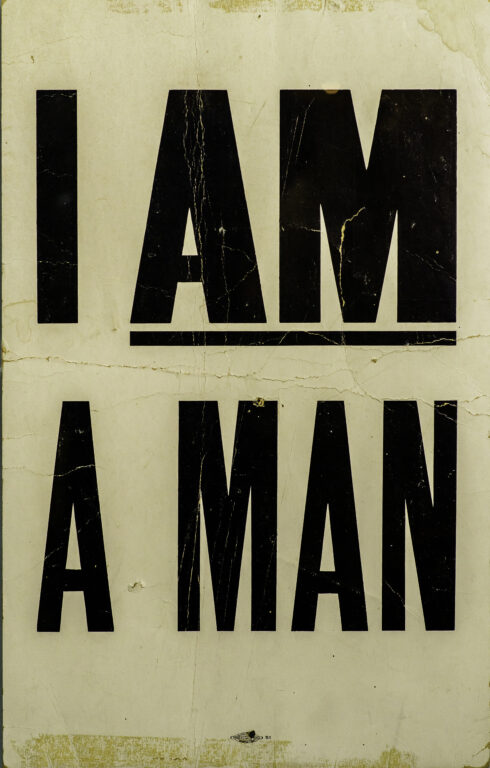

“I AM A MAN” Sign (1968) DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Workers in the 1968 Memphis Sanitation strike carried and wore signs like this one to protest discrimination and abhorrent working conditions. Although the workers’ demands were eventually met, it was while visiting Memphis for this strike that Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated.

Even before King’s death, a more radical arm of the Civil Rights Movement had begun to criticize his approach as too passive. Malcolm X (himself assassinated in 1965) and others spoke in favor of Black nationalism, resistance, and self-determination, paving the way for a new phase in the Movement.

The Black Panthers

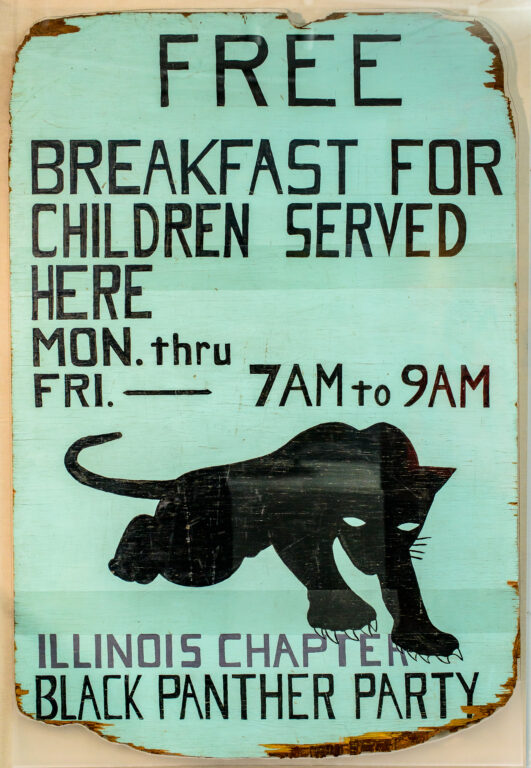

Chicago “Free Breakfast” sign, c 1969 Concerned with issues affecting the black community such as poverty, education, and health care, the Panthers undertook a range of popular grassroots “survival programs.” Among the most successful were the Free Breakfast for Children program, free medical clinics, widespread testing for sickle cell anemia.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in October of 1966. The Panthers rejected the strategy of nonviolent protest and advocated taking up arms to protect their people. While their militancy was highly visible, it was also distorted and vilified by the government and media, often portrayed as a threat to white society. In reality, the organization spent much of its energy on grassroots efforts, seeking to improve quality of life for all African Americans. Panther community programs included free breakfast for children, free medical clinics, and testing for sickle cell anemia.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

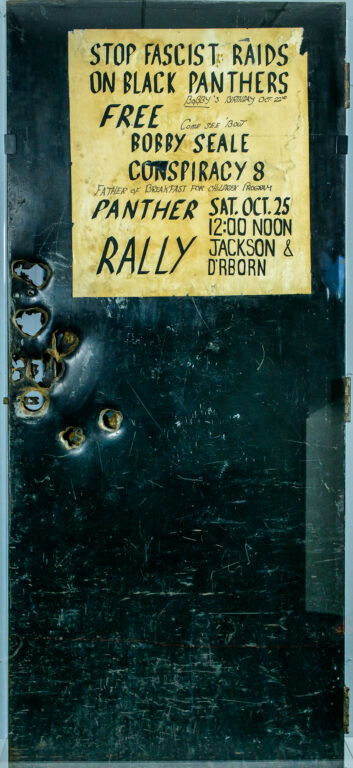

In only three years, dozens of chapters of the Black Panther Party cropped up across the U.S. The group’s rapid growth, however, was hindered by the relentless efforts of the FBI. Its Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) sought to destroy the Party through infiltration, media smear campaigns, and harassment. Key leaders were investigated, imprisoned, and assassinated. In Chicago, FBI and local police conducted a series of raids, including one in October 1969 that riddled the door to Panther headquarters with bullets.

By the early 1980s, leadership disputes and government aggression had led to the Party’s demise.

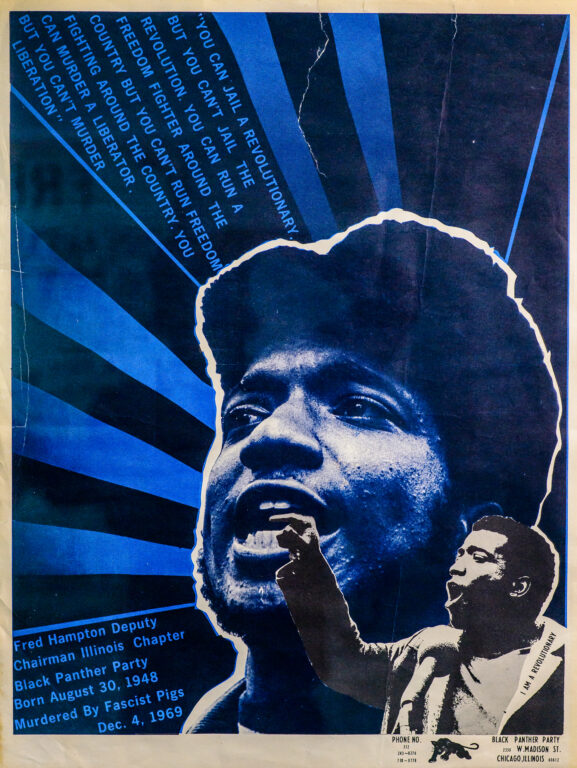

Fred Hampton memorial poster Poster featuring two images of Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton, who was killed in a police raid on December 4, 1969. The poster’s striking graphic composition is enhanced by the use of superimposed images, textual elements, and alternating blue and black rays.

DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

Joining the Black Panther Party at the age of 20, Fred Hampton quickly gained fame as a passionate orator and charismatic leader. Showing a talent for community organizing, he negotiated an alliance between several powerful Chicago gangs and activist groups across racial lines.

As chairman of the Panthers’ Illinois chapter, Hampton organized rallies, taught political education classes, and led several community programs. However, his success made him a prime government target. He was fatally shot in his sleep on December 4, 1969, when Chicago police and federal agents raided his apartment.